Everything you need to know to choose what game to start with

So, Final Fantasy has caught your interest. Who can blame you: with Final Fantasy 14, the MMORPG, outperforming World of Warcraft, and the hype for the single-player action-RPG Final Fantasy 16 at a high, it’s natural you are curious about this storied franchise.

But Final Fantasy is a weird franchise. It’s big and complex and has been around forever. In that time it has developed its own set of conventions that fans understand but aren’t always intuitive to new players.

In this article, we’re going to get you up to speed as painlessly as we can. We’re going to show you all the quirks that make this series special, then demystify them so you can pick your first Final Fantasy game and maybe fall in love with these games like we have.

If you want to skip the background info and know which game you should play first and why, click here.

Contents

Why play Final Fantasy

For over 35 years, the Final Fantasy series has been leading videogames in fully realised fantasy worlds, beautiful music and cutting-edge visuals. It has memorable characters that have become icons, and stories that deliver twists and emotions in equal amounts. And because it recreates itself with almost every instalment, it is a series that is almost impossible to get bored of.

Who plays Final Fantasy?

It is impossible to know how many fans the series has worldwide, but it is probably tens of millions. Here are a few numbers for illustration:

- According to mmo-populations.com, Final Fantasy 14 has over 40 million players.

- Probably the best-selling game in the franchise is Final Fantasy 7, the original PS1 and PC versions selling over 10 million copies.

- For a more recent bestselling game, Final Fantasy 15 also sold over 10 million copies

- The r/FinalFantasy subreddit has 400k subscribers

- The Square Enix YouTube channel has 300k followers.

Reasons for Final Fantasy’s popularity

Games in the Final Fantasy series have regularly been trailblazers for more complex stories and more advanced graphical fidelity in video games. It found worldwide appeal because it helped introduce Western console players to Japanese RPGs.

The series is also known for its music and characters, which linger in people’s minds long after they have finished the game.

Moreover, as a long-running series that has released games consistently since 1987, this series has had a long time to build up a following.

What you need to know

A series of standalone games

The first thing to understand about the Final Fantasy series is that all of the major numbered [jump link] games exist in their own universe, with different characters and unconnected stories.

There are direct sequels in the franchise, such as Final Fantasy 10-2 (a sequel to Final Fantasy 10), but other than these rare cases you can play any major games in the series without having played any others. [optimse as answer tag]

Common elements of Final Fantasy

Or, How to spot Final Fantasy in the wild.

Though the games do not share stories or even worlds, there are themes, ideas, visuals and more that recur across the series and make a Final Fantasy feel like a Final Fantasy game.

Chocobos: Bird-like mounts, most commonly yellow. Introduced in Final Fantasy 2.

Moogles: A race of cute magical creatures with pom-poms on their head that say “Kupo!” They fill various roles across the series. Introduced in Final Fantasy 3.

Crystals: Large magical crystals that play a role in the story, sometimes named after the four elements.

Monsters: Bombs, tonberries, cactuars, malboros and behemoths are some of the more iconic recurring foes, though there are many more.

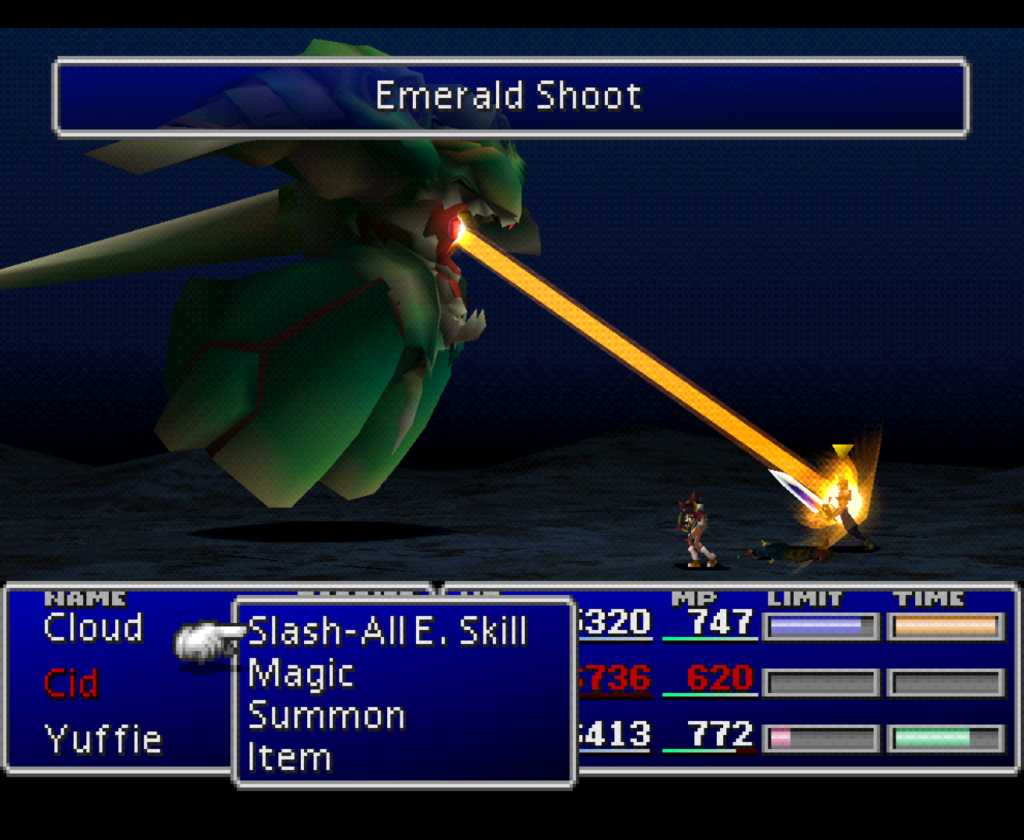

Summons: Powerful creatures that can be called into battle, several of which appear in almost every game, including Shiva the ice queen, Ifrit the fire demon, and Bahamut the dragon. Introduced in Final Fantasy 3.

Jobs/Classes: Combat roles like black mage, white mage, red mage, dragoon and thief have associated design elements across the series. Introduced in Final Fantasy.

Spells: Mages across the series have pulled from a common pool of spells with shared naming conventions, where suffixes like “-ara” and “-aga” indicate more powerful versions of spells (eg. Blizzard, Blizzara, Blizzaga in order of power)

Equipment: Weapons like Masamune and Ultima Weapon are found in multiple games.

Music tracks: Though the games do not generally share music, there are a few exceptions that appear in many games, such as the chocobo theme. In particular, Prelude (or Crystal Theme) and Final Fantasy (or Main Theme) are in many games in the series.

The Roman numerals

Not everyone learns Roman numerals in school, and being a Star Wars fan will only take you up to IX = 9. This method of numbering can make distinguishing the major Final Fantasy games a bit of a challenge for new fans. For clarity, in this article we’ve named the games with Arabic numbers, but here are all the titles in both formats:

| Title (Roman Numerals) | Title (Arabic Numerals) |

|---|---|

| Final Fantasy | Final Fantasy 1 |

| Final Fantasy II | Final Fantasy 2 |

| Final Fantasy III | Final Fantasy 3 |

| Final Fantasy IV | Final Fantasy 4 |

| Final Fantasy V | Final Fantasy 5 |

| Final Fantasy VI | Final Fantasy 6 |

| Final Fantasy VII | Final Fantasy 7 |

| Final Fantasy VIII | Final Fantasy 8 |

| Final Fantasy IX | Final Fantasy 9 |

| Final Fantasy X | Final Fantasy 10 |

| Final Fantasy XI | Final Fantasy 11 |

| Final Fantasy XII | Final Fantasy 12 |

| Final Fantasy XIII | Final Fantasy 13 |

| Final Fantasy XIV | Final Fantasy 14 |

| Final Fantasy XV | Final Fantasy 15 |

| Final Fantasy XVI | Final Fantasy 16 |

Start with these games

We’re going to get into the weeds on this in a minute, and when you’ve read the next few sections you should feel more confident picking a first game for yourself, if you want.

However, to give you the quick answers:

- We think, for the average person, the best starting point is Final Fantasy 10. It is an extremely popular and accessible starting point, a gripping story, and hits the perfect balance of experimenting with the formula while being true to the series’ identity.

- In some ways, Final Fantasy 4 is where the series “became itself”, and features all of the hallmarks seen in the rest of the series. A great place to start if you want a historical perspective but don’t want to go all the way back to Final Fantasy 1 (which you might consider archaic).

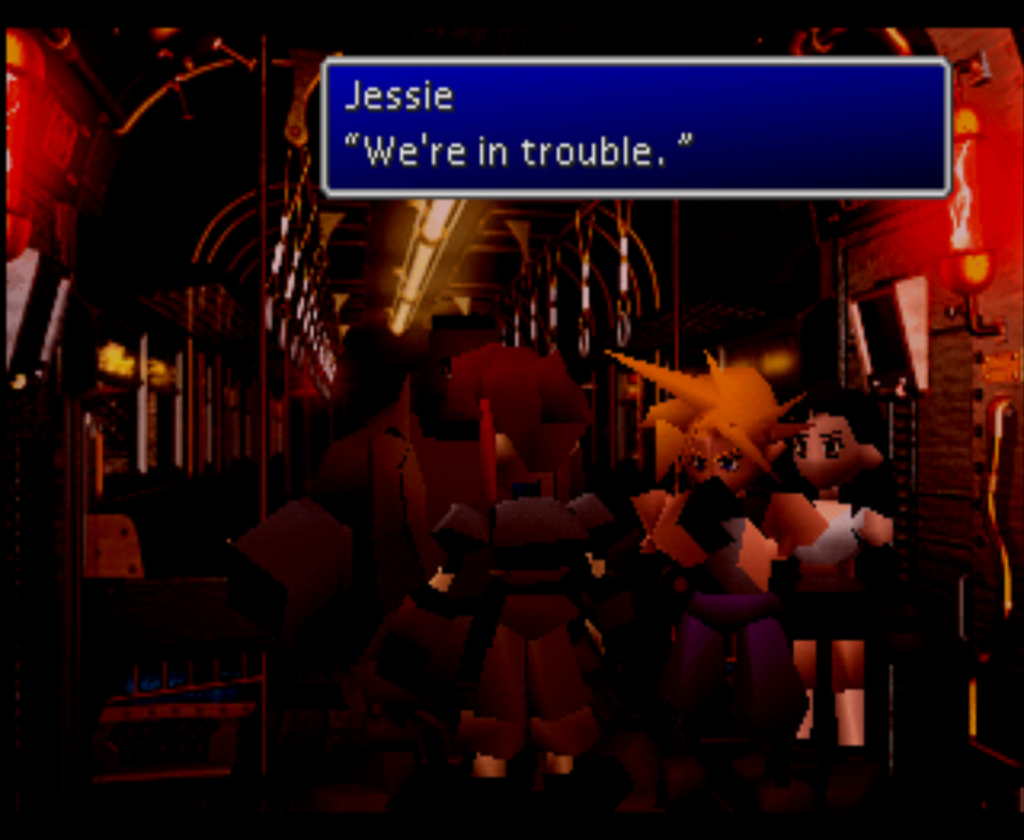

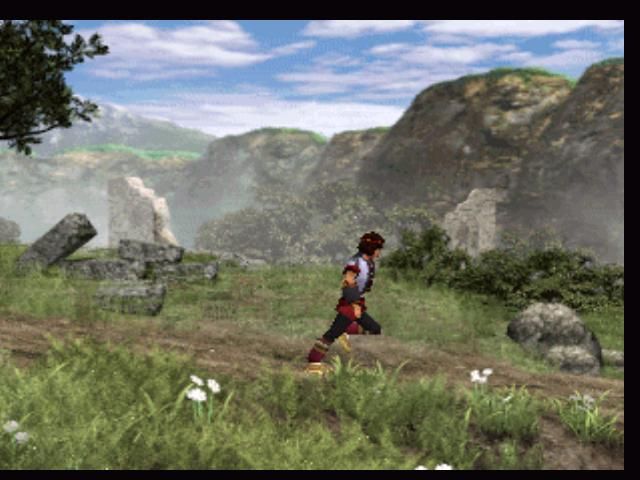

- Final Fantasy 7 is the first 3D game, so a good place to start if you don’t want to play something 2D, and absolutely a historical landmark mark not only for the series, but for Japanese gaming in the West, JRPGs, and gaming as a whole. Don’t miss it.

- Final Fantasy 14 is an MMO, so is not the “standard” Final Fantasy experience, but it is extremely good. Plus, being an absolutely dominant force in the MMO market, it is probably the most popular introduction to the series these days. It also looks a lot more modern than the other starting points mentioned here.

A brief history of the series

The first eleven mainline games were all developed and published by Square.

Final Fantasy 1 to Final Fantasy 6 are 2D games released first on Nintendo hardware. 1-3 were originally released on the Famicom (NES), and 4-6 originally released on the Super Famicom (SNES).

Only Final Fantasy 1, 4 and 6 were released in the US, and 4 and 6 were renumbered as 2 and 3. So if you ever hear somebody refer to Final Fantasy 6 as Final Fantasy 3, this is the reason. It also means that Final Fantasy 2, 3, and 5 were not originally released in the West and so fewer older fans have the same connection with those games that they do for the others.

After this, Square moved the franchise from Nintendo systems to Sony systems, partly as a result of the Playstation using disks over cartridges.

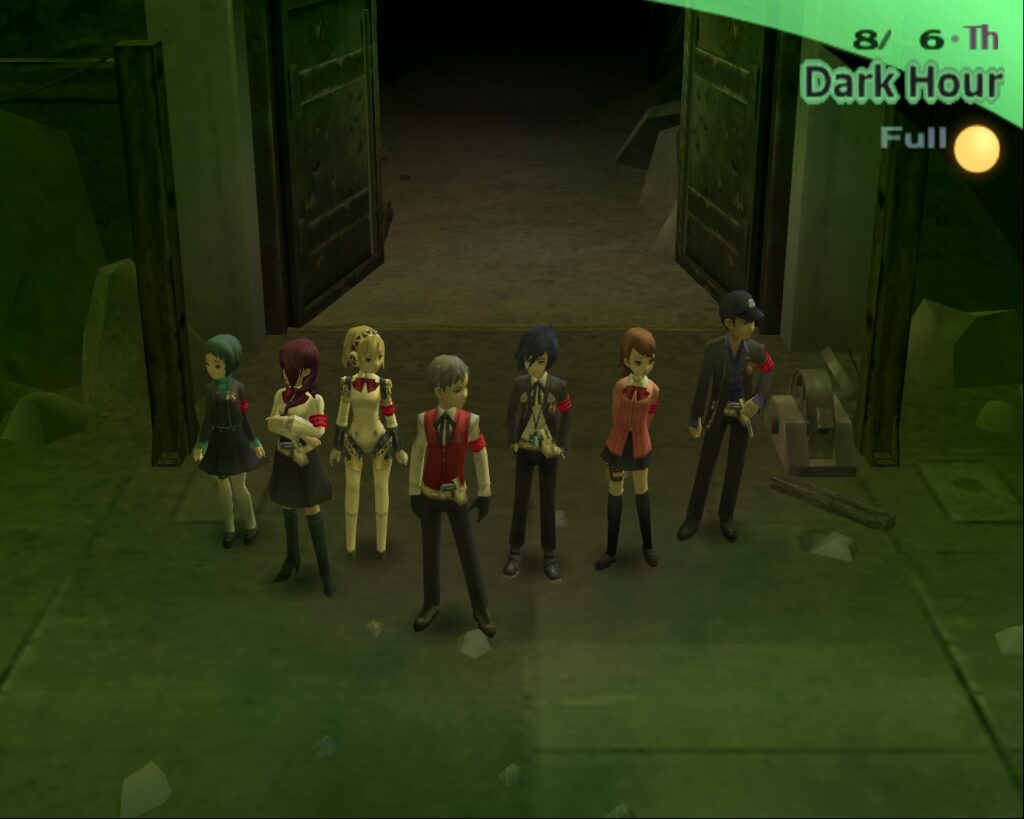

Final Fantasy 7 to Final Fantasy 10 use 3D graphics and were released first on Playstation consoles. 7-9 were released originally on the PS1, and 10 on the PS2.

Though many of the games in this era are beloved bestsellers, the most successful one up to this point was undoubtedly Final Fantasy 7, which was often held up as one of the best videogames, or one of the best videogame stories, ever made.

Final Fantasy Tactics for the PS1 was the most significant spin-off released during this period.

All of the mainline games up to this point were traditional, turn-based JRPGs. After Final Fantasy 10, each game mixed up the formula more than ever before.

Final Fantasy 11 was the first MMORPG of the series and was followed by many expansions.

The first movie in the franchise, Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, was released in 2001. Its inability to recoup its costs became a pivotal moment not only for the franchise but for Square as a company.

Financial difficulties was one reason Square merged with Enix to create Square Enix. Exix were the publisher of the Dragon Quest games, Final Fantasy’s main competitor in the JRPG market.

In the years following the merger, some changes in the series can be identified.

Starting with Final Fantasy 10-2, sequels and prequels to the stories of mainline games became a regular part of the franchise. Sub-series were made to expand the worlds of mainline games, including Compilation of Final Fantasy 7 (new games in the world of Final Fantasy 7) and Ivalice Alliance (new games in the world of Final Fantasy Tactics). New mainline games, starting with 13, were introduced as multi-game or multimedia projects, subseries in their own right.

After 10, each mainline game would reinvent the formula, resulting in games that are more diverse than ever before, being separate not only in their story but also in their mechanics. Final Fantasy 12 removed battle screens and took inspiration from MMOs, whereas 13 brought back battle screens but entirely overhauled ATB and class systems from older games to make something unique.

Final Fantasy 14 was a second MMO that was a critical and commercial failure but was relaunched as Final Fantasy 14: A Realm Reborn and became a massive success.

Final Fantasy 15 was the first mainline game to feature action combat. This direction continued with Final Fantasy 7 Remake and Final Fantasy 16.

And that pretty much gets us up to date!

But that only covers the mainline series. By our count, there are about 100 original Final Fantasy games.

How many games?!

Yep, there are about 100 original Final Fantasy games! It depends on how you count them though. To get this number, we didn’t include ports, compilations or remasters, but did include spin-offs, remakes, and smaller games that are not full-scale JRPGs. [optimse as answer tag]

A few games are in a grey area, such as the Pixel Remasters, that look and play differently than the original games. However, we still choose not to include it in our count. We did include the remakes of Final Fantasy 1 and 2 for the Playstation compilation, as we considered them to have passed a threshold to be counted as new games, and full remakes such as Final Fantasy 3 for the DS and Final Fantasy 7: Remake are also considered by us to be new games.

However you choose to count them, there are rather a lot of games in this series. Let’s try and make a little more sense of these.

Mainline series

There are 15 mainline Final Fantasy games. When fans talk about the mainline series, they mean the games that count up in ascending order from the original game: Final Fantasy, Final Fantasy 2, Final Fantasy 3, and so on. The latest was Final Fantasy 15, which gives us 15 games.

This excludes games like Final Fantasy Tactics and Final Fantasy: Crystal Chronicles, which are considered spin-offs. More about them in a minute.

What makes mainline games special is that they introduce new worlds and characters, and tend to have the largest budgets (and sales) of any other Final Fantasy project of its time. They tend to be the games that push the series forward the most.

Eventually, direct sequels to the mainline games were produced, leading to games with titles such as “Final Fantasy 10-2”. These are also sometimes considered part of the mainline series, but not always. Take Dirge of Cerberus, a third-person shooter that continues the story of the mainline game, Final Fantasy 7. It has very different gameplay from the original game, so people are comfortable calling it a spin-off. We will list the sequels separately.

As you can see, it is down to some interpretation. But here’s a fairly typical list of which games are considered the “mainline Final Fantasy games”:

| Title | Release Date |

|---|---|

| Final Fantasy I | 1987 Dec |

| Final Fantasy II | 1988 Dec |

| Final Fantasy III | 1990 Apr |

| Final Fantasy IV | 1991 Nov |

| Final Fantasy V | 1992 Dec |

| Final Fantasy VI | 1994 Apr |

| Final Fantasy VII | 1997 Jan |

| Final Fantasy VIII | 1999 Feb |

| Final Fantasy IX | 2000 Jul |

| Final Fantasy X | 2001 Jul |

| Final Fantasy XI | 2002 May |

| Final Fantasy XII | 2006 Mar |

| Final Fantasy XIII | 2009 Dec |

| Final Fantasy XIV | 2010 Sep |

| Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn | 2013 Aug |

| Final Fantasy XV | 2016 Nov |

| Final Fantasy VII | 2020 Apr |

| Final Fantasy XIV | 2021 Dec |

| Final Fantasy XVI | 2023 Aug |

Sequels and prequels

The Final Fantasy franchise resisted sequels for a long time, choosing to create new worlds with new characters with each new game. This changed with Final Fantasy 10-2, which reused the assets of Final Fantasy 10 to tell a sequel to that story.

Since then, stories that spin off from mainlines titles have become a common element of the franchise, and some games have even been announced as multiple-game series from the start. We have also included expansions to the MMO games.

| Title | Type | Release Date |

|---|---|---|

| Final Fantasy X-2 | Sequel | 2003 Mar |

| Final Fantasy XI: Rise of the Zilart | Expansion | 2003 Apr |

| Final Fantasy XI: Chains of Promathia | Expansion | 2004 Sep |

| Before Crisis: Final Fantasy VII | Prequel | 2004 Sep |

| Dirge of Cerberus: Final Fantasy VII | Prequel | 2006 Jan |

| Final Fantasy XI: Treasures of Aht Urhgan | Expansion | 2006 Apr |

| Final Fantasy XII: Revenant Wings | Sequel | 2007 Apr |

| Crisis Core: Final Fantasy VII | Prequel | 2007 Sep |

| Final Fantasy XI: Wings of the Goddess | Expansion | 2007 Nov |

| Final Fantasy IV The After Years | Sequel | 2008 Feb |

| Final Fantasy XIII-2 | Sequel | 2011 Dec |

| Final Fantasy XI: Seekers of Adoulin | Expansion | 2013 Mar |

| Lightning Returns: Final Fantasy XIII | Sequel | 2013 Nov |

| Final Fantasy XIV: Heavensward | Expansion | 2015 Jun |

| Final Fantasy XIV: Stormblood | Expansion | 2017 Jun |

| Final Fantasy XIV: Shadowbringers | Expansion | 2019 Jul |

| Final Fantasy VII: The First Soldier | Prequel | 2021 Nov |

| Final Fantasy XIV: Endwalker | Expansion | 2021 Dec |

Remakes

Final Fantasy games are regularly ported and remastered for new systems, but sometimes the franchise goes a step further with full remakes that substaintially change the visuals and mechanics.

| Title | Platform | Release Date |

|---|---|---|

| Final Fantasy I | WonderSwan Color | 2000 Dec |

| Final Fantasy II | WonderSwan Color | 2001 May |

| Final Fantasy III | Nintendo DS | 2006 Aug |

| Final Fantasy IV | Nintendo DS | 2007 Dec |

| Final Fantasy VII Remake | PlayStation 4 | 2020 Apr |

| Final Fantasy VII: Rebirth | Playstation 5 | 2023 Dec |

Sub-series

There are a few groups of games that were given unique branding to distinguish them as their own sub-series. This extended beyond videogames, as these subseries also included films and short stories, such as the second movie in the franchise, Final Fantasy 7: Advent Children.

- Compilation of Final Fantasy 7

- Ivalice Alliance

- Fabula Nova Crystallis

Spinoffs

All games with Final Fantasy in the title that are not considered mainline titles (subject to interpretation) are spin-offs.

Some spin-offs become Final Fantasy sub-series, or even entirely new series without the Final Fantasy name.

The first spin-off was The Final Fantasy Adventure, which is also a great example of a spin-off that became a new series. It was known as Seiken Densetsu: Final Fantasy Gaiden in Japan, but for the next game dropped the Final Fantasy moniker and became the Seiken Densetsu series, which in the West was called the Mana series. The first game using the Mana title was Seiken Densetsu 2, or Secret of Mana.

Another notable early spin-off was Final Fantasy Mystic Quest, which is best remembered as an attempt to make an RPG that was accessible to new players, but ended up disappointing Final Fantasy fans for being easy and shallow.

Like Mystic Quest, most spin-offs keep the Final Fantasy branding, even if they become their own series. Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles, for example, was conceived as a Final Fantasy game with a co-op focus. It spawned sequels, each with its own subtitle, leading to games with long names like Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles: Ring of Fates.

The following tables is dedicated to spin-offs that feature original characters. For the spin-offs that focus on the heroes introduced in mainline games, look at the crossovers section below.

Here are the major Final Fantasy spin-offs:

| Name | Release Date |

|---|---|

| Final Fantasy Adventure (Final Fantasy Gaiden) | 1991 Jun |

| Final Fantasy Mystic Quest | 1992 Oct |

| Final Fantasy Tactics | 1997 Jun |

| Final Fantasy Tactics Advance | 2003 Feb |

| Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles | 2003 Aug |

| Final Fantasy Tactics A2: Grimoire of the Rift | 2007 Jun |

| Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles: Ring of Fates | 2007 Aug |

| Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles: My Life as a King | 2008 Mar |

| Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles: Echoes of Time | 2009 Jan |

| Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles: My Life as a Darklord | 2009 Jun |

| Final Fantasy: The 4 Heroes of Light | 2009 Oct |

| Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles: The Crystal Bearers | 2009 Nov |

| Final Fantasy Dimensions | 2010 Sep |

| Final Fantasy Type-0 | 2011 Oct |

| Final Fantasy Tactics S | 2013 May |

| Final Fantasy Explorers | 2014 Dec |

| Mobius Final Fantasy | 2015 Jun |

| Final Fantasy: Brave Exvius | 2015 Oct |

| World of Final Fantasy | 2016 Oct |

| Final Fantasy Awakening | 2016 Dec |

| Final Fantasy Dimensions II | 2017 Nov |

| War of the Visions: Final Fantasy Brave Exvius | 2019 Nov |

| Final Fantasy VII: The First Soldier | 2021 Nov |

| Stranger of Paradise: Final Fantasy Origin | 2022 Mar |

Crossover Spinoffs

Perhaps inspired by the success of crossover games like Super Smash Bros, Square Enix created the fighting game Dissidia. It was the first time existing characters from mainline games had come together to share a story.

Since then, Final Fantasy crossover games have been released regularly. This category includes Theatrhythm, a series of rhythm games that use Final Fantasy music, as well as a number of gatcha games where players summon characters from across the franchise.

| Name | Release Date |

|---|---|

| Dissidia Final Fantasy | 2008 Dec |

| Dissidia 012 Final Fantasy | 2011 Mar |

| Theatrhythm Final Fantasy | 2012 Feb |

| Final Fantasy Artniks | 2012 Nov |

| Final Fantasy: All the Bravest | 2013 Jan |

| Pictlogica Final Fantasy | 2013 Oct |

| Theatrhythm Final Fantasy: Curtain Call | 2014 Apr |

| Final Fantasy Record Keeper | 2014 Sep |

| Dissidia Final Fantasy NT | 2015 Nov |

| Dissidia Final Fantasy Omnia | 2018 Jan |

| Theatrhythm Final Fantasy: All-Star Carnival | 2016 Sep |

| Theatrhythm Final Bar Line | 2023 Feb |

Spinoff Series

As you can see, some spin-offs have sequels and become their own subseries. Here are the major spin-off series along with the number of titles that have been released in those

| Series | Numbers of Games |

|---|---|

| Crystal Chronicles | 6 |

| Dissidia | 4 |

| Tactics | 4 |

| Theatrhythm | 4 |

| Dimensions | 2 |

| Brave Exvius | 2 |

Which are the best Final Fantasy games?

That’s an excellent question, and a really tricky one. Every game is somebody’s favourite. Plus, different games rise and fall in popularity over time. But we’re here to give answers. If there were only 10 gold stars to give out to games in this franchise, we might suggest a list that looks like this:

- Final Fantasy 4

- Final Fantasy 5

- Final Fantasy 6

- Final Fantasy Tactics

- Final Fantasy 7

- Final Fantasy 8

- Final Fantasy 9

- Final Fantasy 10

- Crisis Core: Final Fantasy 7

- Final Fantasy 14

With this list, we are trying to distil the impossible-to-measure “common feeling” about the game among fans, based on informal conversions in fan communities as well as public surveys. You might say we are trying to emulate a popularity contest.

“The classics” have a lot of weight in this sort of list. Though Final Fantasy 4 and 5 are both important and beloved, a new player might find them less compelling than more modern games in the series.

Nonetheless, this list gives a great selection of games to play if you want to understand what the franchise is about and what makes it great. It tells you what the best the franchise has had to offer over time.

This does not mean that the games not on this list can’t be excellent, nor that playing a game on the list is a guarantee of a good time.

And the best-selling ones?

It’s impossible to give exact sales numbers, but here are the current estimates as calculated by VGChartz:

| Game | Sales (VGChartz) |

|---|---|

| Final Fantasy 10 | 20.8 M |

| Final Fantasy 7 | 14.1 M |

| Final Fantasy 15 | 10 M |

| Final Fantasy 8 | 9.6 M |

| Final Fantasy 13 | 7.71 M |

| Final Fantasy 12 | 7.71 M |

| Final Fantasy 9 | 5.83 M |

| Final Fantasy 7 Remake | 5 M |

| Final Fantasy 3 | 3.86 M |

| Final Fantasy 6 | 3.81 M |

Notes: Final Fantasy 10 includes the sales of the Final Fantasy 10|10-2 collection.

In addition to these sales numbers, some estimates put the number of active Final Fantasy 14 players at 40 million+, which would almost certainly put it at the top of this list. Square Enix has confirmed that 14 is the most profitable game in the series.

Final Fantasy genres

Final Fantasy games have featured a range of combat mechanics and game structures, starting as semi-linear adventures with strict turn-based combat. Soon, a real-time element was introduced into the battles. As the series got more experimental, the game structure varied from highly linear to open-world, and the battles were more strategic in some games, and full-on action in others.

The mainline series changed slowly, whereas spinoffs turned Final Fantasy into everything from an RTS to a multiplayer fighting game.

Here are the mainline games and a selection of the spinoffs along with their battle mechanics, which are explained in more detail below:

| Title | Battle System |

|---|---|

| Final Fantasy I | Turn-based |

| Final Fantasy II | Turn-based |

| Final Fantasy III | Turn-based |

| Final Fantasy IV | Active menu-driven |

| Final Fantasy V | Active menu-driven |

| Final Fantasy VI | Active menu-driven |

| Final Fantasy VII | Active menu-driven |

| Final Fantasy Tactics | Turn-based strategy |

| Final Fantasy VIII | Active menu-driven |

| Final Fantasy IX | Active menu-driven |

| Final Fantasy X | Turn-based |

| Final Fantasy XI | Cooldown-based |

| Final Fantasy X-2 | Active menu-driven |

| Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles | Action |

| Dirge of Cerberus: Final Fantasy VII | Third-person shooter |

| Final Fantasy XII | Active menu-driven (in-field) |

| Final Fantasy XII: Revenant Wings | Real-time strategy |

| Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles: Ring of Fates | Action |

| Crisis Core: Final Fantasy VII | Action/menu-driven hybrid |

| Final Fantasy IV: The After Years | Active menu-driven |

| Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles: My Life as a King | City-building |

| Dissidia: Final Fantasy | Fighting game |

| Final Fantasy XIII | Active menu-driven |

| Final Fantasy XIV | Cooldown-based |

| Final Fantasy Type-0 | Action |

| Final Fantasy XIII-2 | Active menu-driven |

| Lightning Returns: Final Fantasy XIII | Action/menu-driven hybrid |

| Final Fantasy XV | Action |

The Turn-Based Final Fantasy Games

In the early Final Fantasy, combat took place in turns. You choose your actions (physical attacks, spells and item usage) from a menu, your character performed that action, then the your opponent, usually a monster, would have their opportunity to fight back while your characters stood still.

Turn-based is closely related to the “ATB” games.

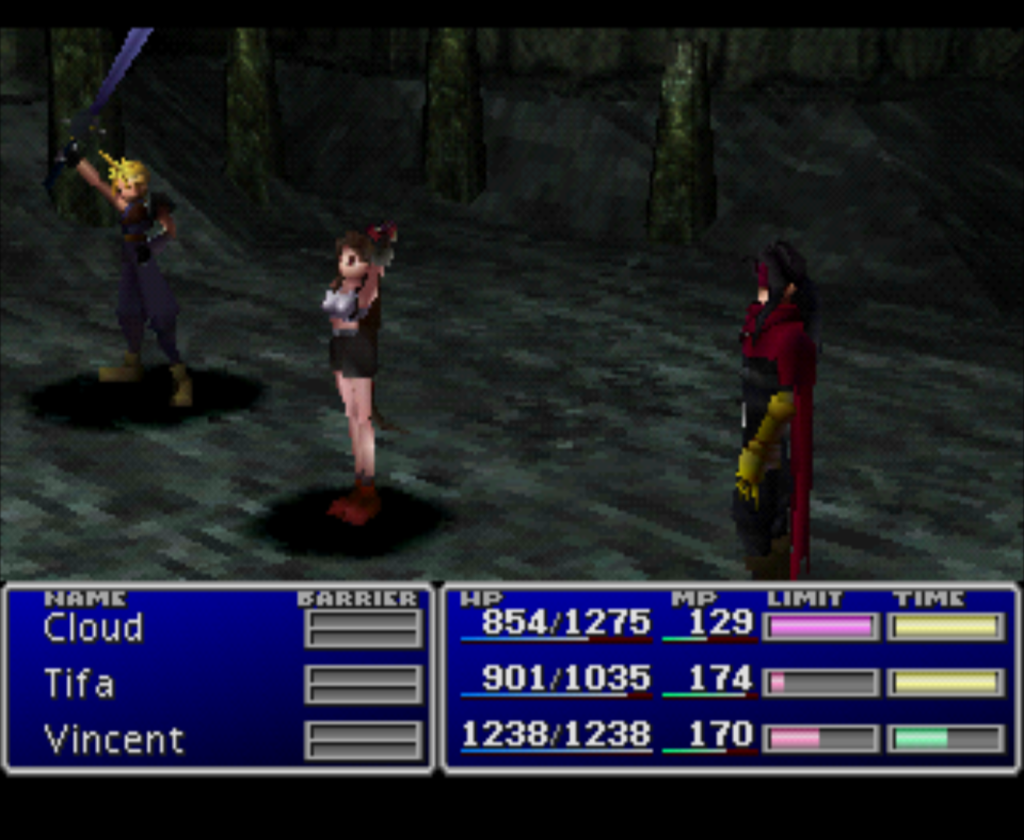

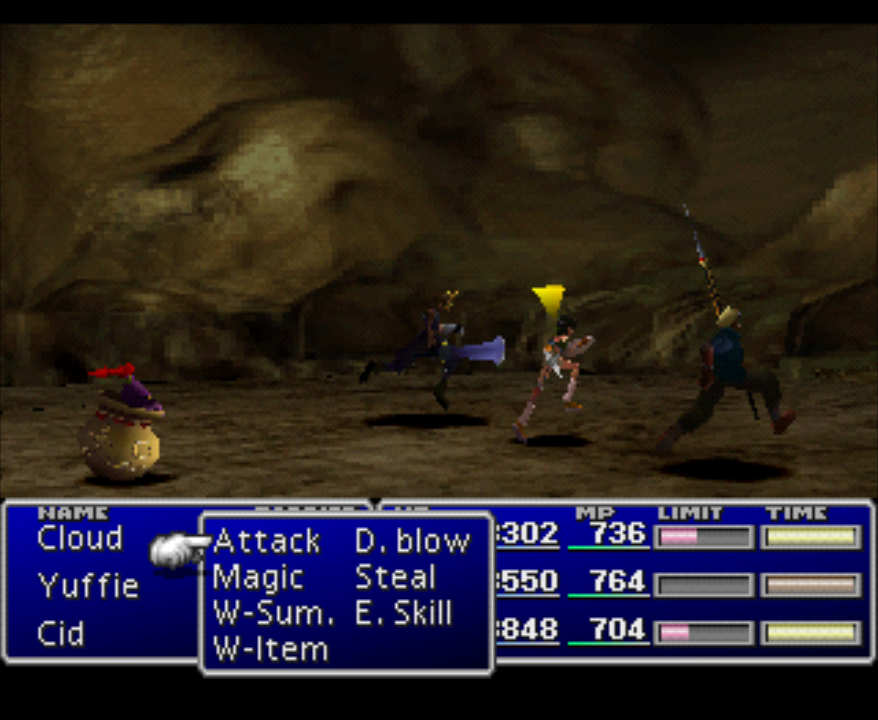

The Action-Time Battle (ATB) Final Fantasy Games

One way to describe ATB is a menu-based battle system with cooldowns for each character and enemy after they act. “Real-time turn-based” also gives the right idea.

In practice, it looks and feels very similar to turn-based, but enemies will still get their turns and attack while you are choosing your commands. It was introduced in Final Fantasy 4 and was used in all mainline Final Fantasy games until Final Fantasy 10. Many spin-off games also used this system.

The Action Final Fantasy Games

The series added real-time elements early on but has only made the jump to full-on action gameplay on occasion. It is becoming more common, though, and now multiple games in the mainline series have thrown away the menu-based battles and have combat in the style of an action game. This has caused consternation for long-term series fans.

The MMO Final Fantasy Games

The two Final Fantasy MMOs are mainline, numbered Final Fantasy games: Final Fantasy 11 and Final Fantasy 14. As well as fitting into the “mainline” bucket, they also deserve to be discussed in their own category.

What makes these games different is that you explore a world that is filled with thousands of other players across the world, and you can join up with those players in multiplayer parties to take on the game’s challenges. Both of these MMOs require their own subscription. They each have multiple expansions, which add up to huge amounts of content that will take much longer to play through than any other single game in the series.

Related games and series

We already mentioned the sub-series and the Final Fantasy Adventure/Mana games which turned into their own series. Here are more games that are not part of Final Fantasy but do have connections.

- Kingdom Hearts has Final Fantasy characters as NPCs and even bosses.

- Chrono Trigger is not part of the Final Fantasy series but was made by Square. It is common to hear people joke that Chrono Trigger is their favourite Final Fantasy game.

Conclusions

Phew! If you’ve read this far, you’ve seen that the Final Fantasy series is big and multifaceted, but you’ve also learned that there is a core of mainline games that push the series forward as well as the vast number of spin-offs that take the series in other directions.

You have a better understanding of each of the games in context, and you won’t be completely in the dark when people are talking about XIV this and VII that, because you have the context.

The context isn’t everything though, and the way to learn more is to start playing. Good luck and have fun!