Romancing Saga 2 is a JRPG that all fans of the genre should try. However, there are various versions of it to choose from, and each has mechanics that can confound even experienced gamers.

This guide is designed to get anyone started on any version of Romancing Saga 2, so that more players can appreciate this underrated classic.

Why play this game

Romancing Saga 2 is unlike any other JRPG you have played before or will again. It does have similarities to other SaGa games, specifically it is a hardy challenge and is full of clever and nuaced systems for you to get to grips with, but it goes further than that.

What sets Romancing Saga 2 apart is the generation mechanics, where you have no main character but play as a bloodline of Emperors, each carrying on the game when their ancestor dies or succeeds in enough quests. The results is a game that is rewarding to learn and epic in the true sense of the word.

Romancing Saga 2 may be the first masterpiece of director Akitoshi Kawazu, who also worked on the first two Final Fantasy games and directed most other games in the Saga series. Because the original version of the game was not released in English, Romancing Saga 2 is lesser-known in the west, but the recent 3D remake is changing that.

Versions explained

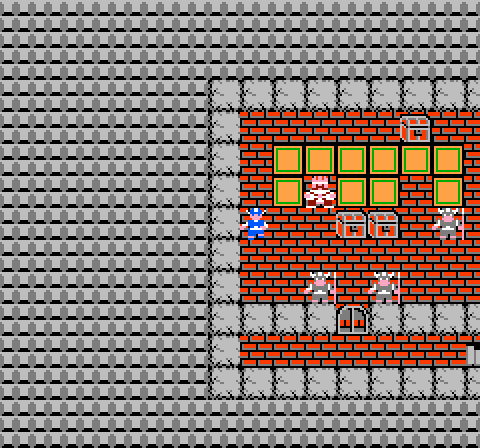

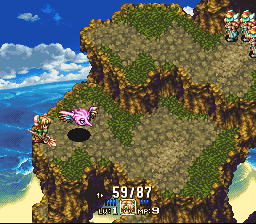

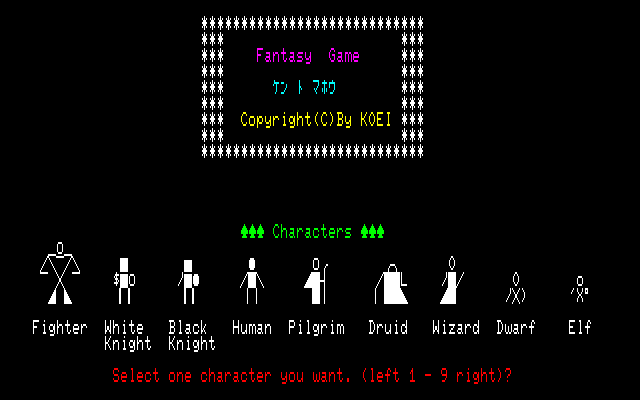

Super Famicom – Japanese Only, No Fan Translation

The original, released in 1993. It’s the great game described above, including the glitches and inconveniences that were updated in later editions.

Romancing Saga 2 for the Super Famicom can be emulated, but as of last checking, there was no complete fan translation. You can check the progress of the furthest along fan translation here: Romhacking.net – Translations – Romancing SaGa 2.

So, do we recommend planing this version of the game? For non-Japanese speakers:

As there is no translation, we do not recommend the Super Famicom version.

For Japanese speakers:

We recommend the super Famicom version only for those with a historical interest in the original, but most players will prefer the remaster.

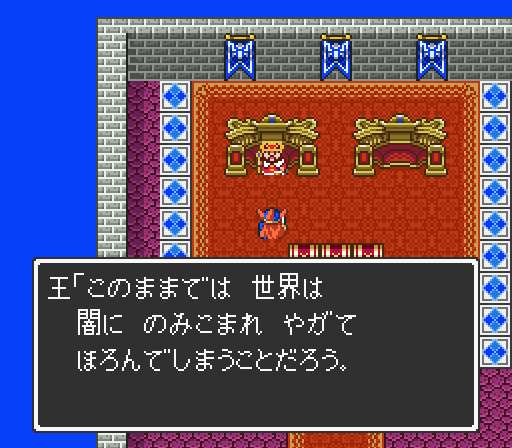

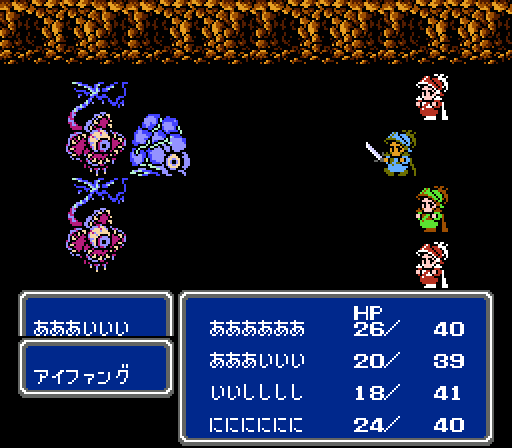

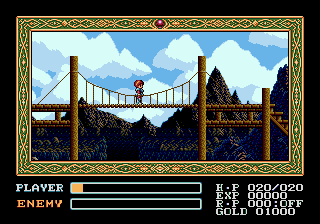

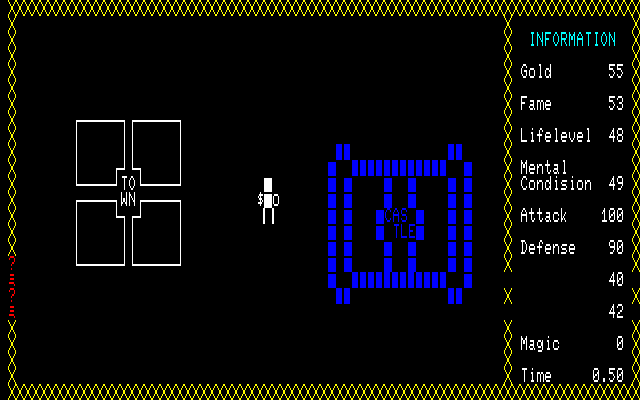

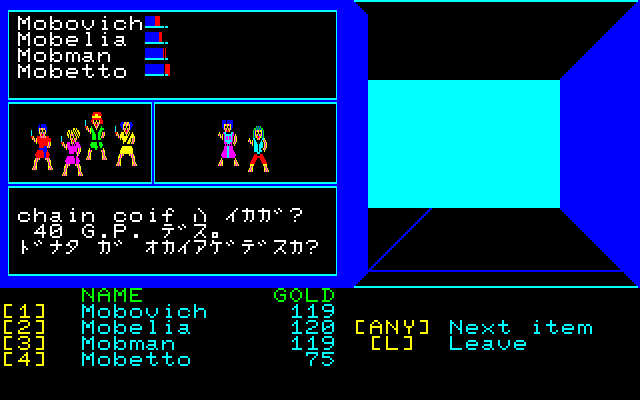

“Remaster” – Mobile, PC and Consoles

Also released as simply Romancing Saga 2, but commonly referred to as the remaster, the 2016 version was produced for mobile first and later ported to many other systems.

The remaster is very faithful, for better at worse. It is mechanically almost identical to the orignal, retaining the difficulty and hidden stats. It adds additional dungeons, most significantly the Maze of Memories, new classes, and allows the player to save any time out of battle, features which may make the game easier if they are used.

Graphically, the remaster uses the original sprites for characters and enemies, but entirely redrawn, high-resolution backgrounds and new attack effects. It is an effective compromise, reusing the original’s best pixel art but making the changes needed for the game to look good on modern screens.

We recommend the remastered version for an accessible experience close to the original game.

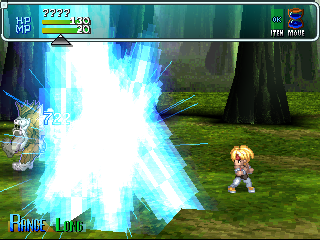

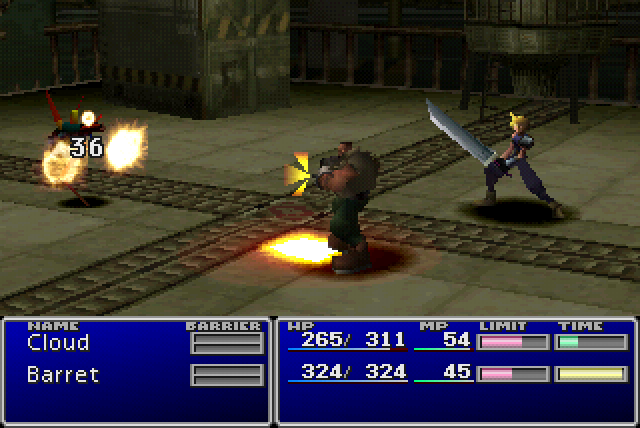

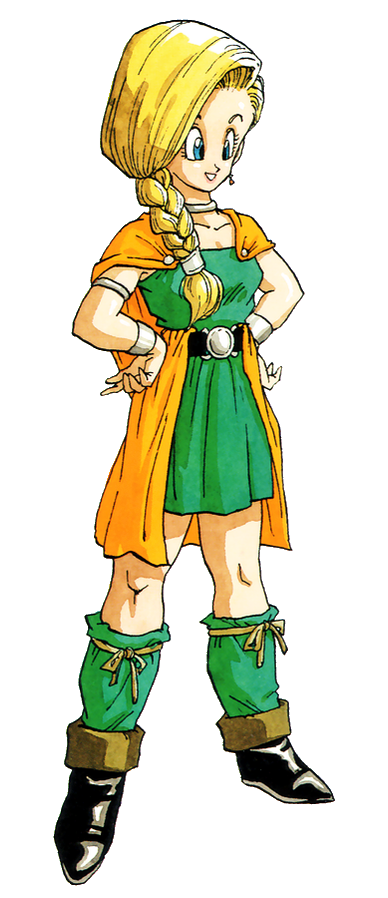

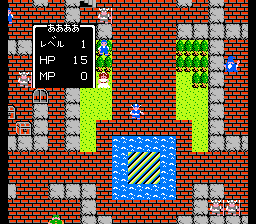

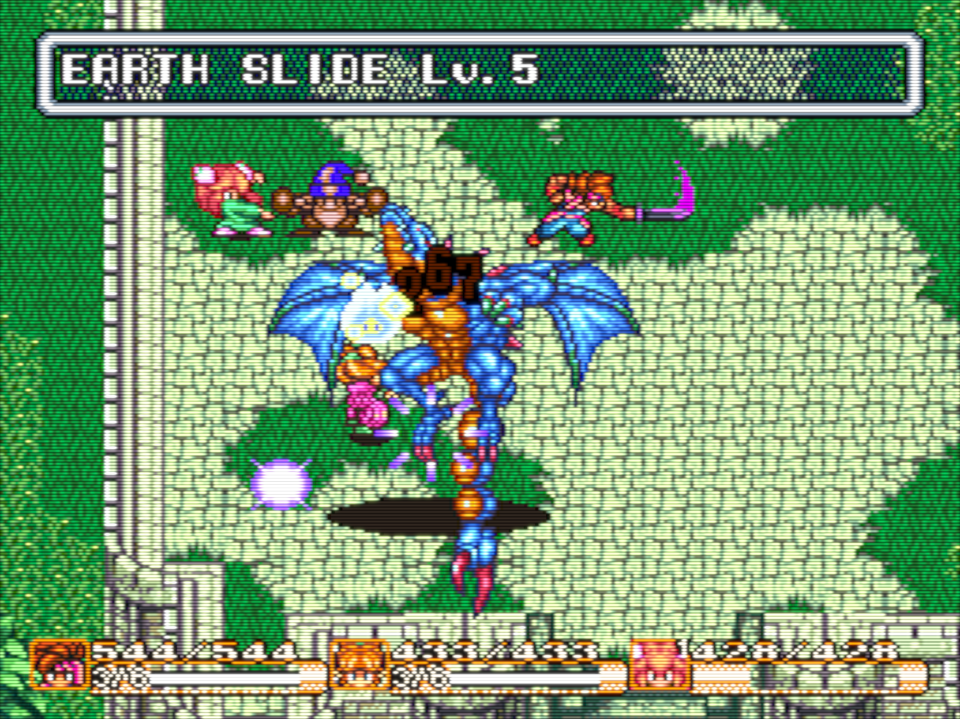

“Remake” – Revenge of the Seven

Images from rpgfan.com

Romancing Saga 2 was, in a way, the next game in the Saga series in line for a remake, as Romancing Saga had already been remade. Still, Revenge of the Seven seemed to come out nowhere — after all, Minstrel Song, the remake of of the previous game in the series, came out almost 20 years earlier!

The spites are gone, replaced with attractive and well-considered 3D models. The complex systems are still there, but the accessibility of them is improved pretty much by a hundredfold: information that was hard to find in the original, or entirely hidden, is fully open to the player via a range of new sub-menus, including magic levels and the development levels of your kingdom.

We recommend the remake for almost everyone, unless you want to play a more faithful experience first.

This unexpected remake has reignited interest in the title. As one of the grandest and most intriguing JRPGs of the SNES era, Romancing Saga 2 getting a remake is justice being done, and by almost all accounts it got the remake it deserved.

Getting Started in the Original or Remaster Versions

Beginner Tips

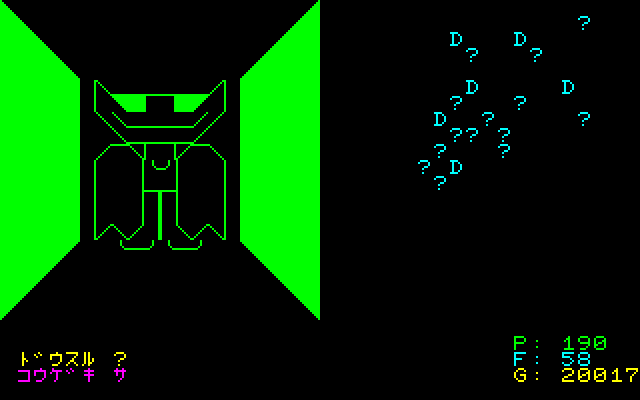

❌ This isn’t Final Fantasy. Your JRPG expectations will be challenged almost immediately, from the way HP is recovered after battle, to how characters can die permanently if they lose all of their LP. Give this game a chance for at least a few hours to get used to it.

👪 Formations matter, and running into an enemy breaks it. There’s no randomness to this. The buffs you get from staying in formation will help you get through those initial battles more smoothly.

🏃 You don’t need to fight every battle. Most areas features enemies in a range of difficulties: you’ll find some you will some stomp, others that are highly unsafe, and everything in between. Running is always successful, except for bosses, so choose your battles.

🕊️ Don’t get anxious about LP. Yes, characters can die permanently, but they will be replaced one way or another anyway. Try an conserve LP, reload if things go really badly, but don’t try to be a perfectionist.

📖 The game won’t hold your hand, so the best way to get started is to read the manual. Some of the tips on this page are found in the manual too, but we still think they’re worth repeating. The most important pages in the manual are…

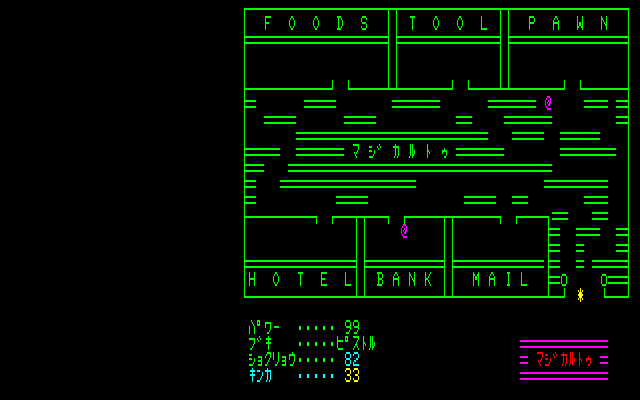

🏰 How each room in the castle works. Seriously, don’t skip this.

🤯 The lack of direction after a few hours may come as a surprise. Things start linear, but the game progressively opens up. Even the hints from your advisor run dry about halfway through the game. It will mostly be down to you to find the paths to new areas, investigate the situation in each area, and decide for yourself which areas you can tackle right now.

💬 Talk to everyone. Like all JRPGs, this is how you get hints. Unlike most other JRPGs, this is also one way you get access to new areas to your map. For making progress, talking is as important as fighting battles!

Intermediate Tips

🕰️ What to know about time skips. When you pick a new Emperor after a time skip, it might look like you’re starting largely from scratch. Actually, you’re not, and in some ways you will be better off after a few years have passed. 1) Skills learned by one character get registered in the dojo to be learned by any or all of your new team. 2) Armour and weapons researched by your blacksmith will now be available in bulk, and new characters might already have the upgraded equipment when you recruit them. 3) New classes you befriended are now available to recruit, and characters of all classes will be more powerful when you recruit them. 4) When you have the magic school, new fusion magic you started researching will finally be available to learn. There are also many things that carry over even though your characters themselves don’t: a big one is that equipment they were carrying gets moved to the storeroom, so don’t forget to make a visit there at the start of a new generation to get your best weapons and armour back.

💡 What to know about learning skills. You’ve realised that the lightbulb in battle means your guy or gal learned a new skill. It’s worth knowing that regular attacks “spark” the widest range of new skills. There are some exceptions — skills that can only be learned with a specific weapon or by using a specific other skill — but for the most part focus on using regular attacks if you’re searching for more of those lightbulb moments.

👹 What to know about battle count. Battle count goes up wherever a battle occurs (even if you immediately run from it). For each battle, you receive your kingdom’s revenue (again, even if you flee). Downside is that the higher the battle count, the stronger the enemies. Don’t panic, it’s a slow process. But to keep up, you do need keep your team’s strength increasing. The next tip will tell you how to do so.

🥾 Focus a little more on exploration and making progress, a little less on grinding battles. The reasons for this are based on various game systems, but to keep it short: there are some essential things you need to get from battles including skill levels, sparking new skills, and money. But for long term progress, these are less important than finding new equipment in chests, researching new buildings, paying the blacksmiths, and expanding your empire into new lands. Don’t rely on grinding to get stronger.

💪 Don’t underestimate yourself. Some areas are absolutely worth avoiding until later generations, but some that seem hard might just require a change in tactics or equipment. Your gaming instinct to “come back later” when enemies seem too hard might need recalibration for this game. Choose when to be stubborn.

✨ Utility spells shouldn’t be underestimated either. Status ailments like stun will swing battles in your favour, especially in the early game. Defensive spells will take away the bite of powerful enemies in the late game. Need a more specific example? Put your healers under a Water Veil in tough battles. You’ll keep them alive so they can keep everyone else alive.

⚔️ Equipment has hidden stats that can be very important. An example given in the manual is that helms are more effective against bash attacks, which isn’t reflected in their defence value. The defence value actually only covers defence against slash attacks, but there are many other types of damage, including hot and cold damage. You can increase your survivability dramatically with this knowledge!

🥋 Armour weight effects how quickly characters act in battle. So when this manual pagetalks about armour being heavy or light, it’s talking about the speed penalty:

🧘 Patience and experimenting are good mindsets. Whether it is a new armor, spell, formation or plan in battle, you can find all the tools you need to succeed in this game. Some tools are extremely powerful, but you need to be willing to play around with things and find them.

Further Reading

Based on the original Super Famicom version, this guide has told players everything they could want to know about the game mechanics, with plenty of screenshots: romancing-saga-2.blogspot.com