Magical healers have had a role in mythology, religion and fantasy literature since forever. You’ve heard of Jesus of Nazareth? Total healer.

We will come back to him later. In role playing games, healers were there even before computers. The first edition Dungeons and Dragons (1974) gave rules for three types of characters: fighting men, magic-users, and clerics. It is the latter that concerns us.

The roster of curing classes expanded in the expansions. In Dungeons & Dragons Supplement I: Greyhawk, the paladin made his RPG debut. In Supplement III: Eldrich Wizardry, we meet the druid for the first time. Rangers and bards also had restorative spells or abilities, to a lesser extent.

These classes were the foundations for in early CRPGs. Thus in the Ultima series we find Dupre the paladin and Jaana the druidess, some of the earliest named healers in videogames.

We can draw a line from these healing trailblazers to the world of JRPGs — starting, as many things do, with Dragon Quest.

Moonbrooke: The start of an archetype? (1987)

This female princess cleric establishes norms many other would abide by, yet most people don’t even know her name.

At least, not a consistent one. She is known as the Princess of Moonbrooke, and in later appearances has the name Purin (after “pudding”), or Princessa in the west — usually.

In the game she hails from, Dragon Quest II, her name is randomly generated, a holdover from pen and paper RPGs where parties were rolled, not pre-written.

What the game does tell us about her is that she is a princess of Moonbrooke castle, she is beautiful, and before she joins the party she is stolen away by the game’s main villain. And if that all sounds about right for a JRPG healer, well, we’re off to a flying start.

The JRPG healer stereotype

In Moonbrooke we see a number of traits that make up the stereotypical main healer of a JRPG party. Such characters, which pop up all across the genre, have most or all of the following traits:

- a young adult women with striking looks

- with a kind and timid personality

- with low physical attacking ability but high magical power

- has royal lineage or some other destiny by birthright

- is often the love interest for the male main character

How did this stereotype come to be? We’ll explore that, but first let’s look at some other examples that show that not all early JRPG healers fit into this box.

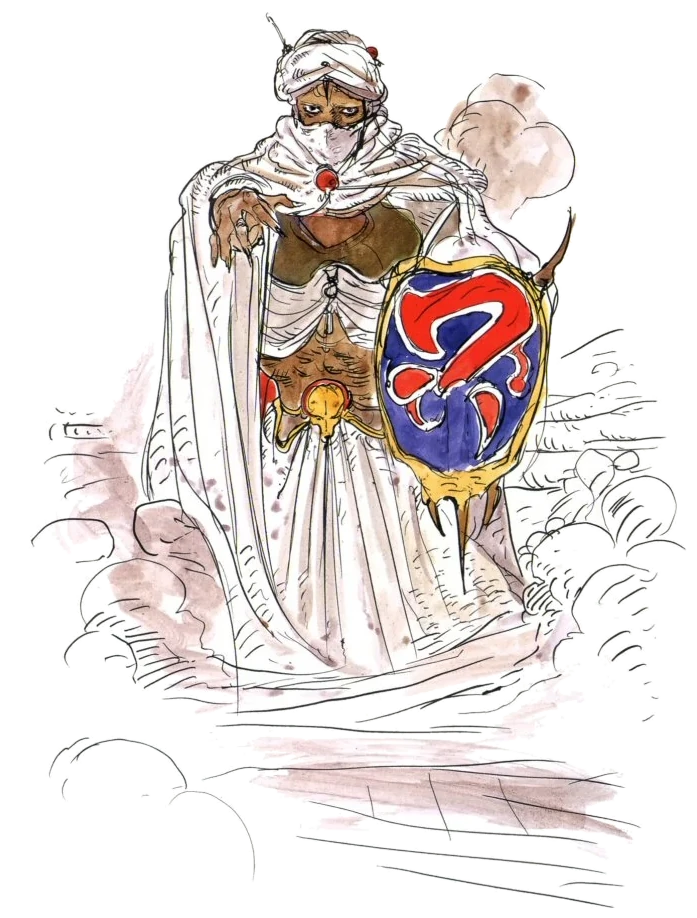

Minwu: The first white mage (1988)

The primary healing class in Final Fantasy is the white mage. The white mage has had a place in the series since the very first game, in which they could be promoted into a white wizard, who, though nameless, had a vaguely masculine look to them.

The first named white mange in the series debuted in the sequel, Final Fantasy II. Winwu is a very different looking first healer than Moonbrooke in Dragon Quest II — and why wouldn’t they be? In the context of the the non-prescriptive nature of Dungeons & Dragons character creation, which these games were inspired by, the ranks of clerics would be filled by all types of people with all backgrounds.

Winwu is experienced in battle by the time the party meet him. He is a mentor to the party and willing to lay down his life for the rebel cause. This committed and hardened character feels uncommon for somebody in his role.

A battle medic needs to get their hands dirty; Minwu is one of the few healers in the series that makes us believe that he would.

Expanding casts (1990-91)

As the size of the casts of JRPG expanded — from a measly one in Dragon Quest (1986), to eight in Dragon Quest IV (1990) — games found room for multiple healers. In Dragon Quest IV, we see two very different, but equally traditional, archetypes: that of a paladin and a cleric.

Kiryl: A paladin appears

Games and stories often feature a connection between healing and religion: the skill is the domain of priests. This connection is intuitive, as such professions centre on supporting members of their community. It is somewhat mystifying that fantasy communities do not have dedicated doctors, but only religious men moonlighting — but I digress. Let us introduce our first priest.

Kiryl is steadfast in his devotion to his god, which contributes to the main joke of his character: the tension between his physical attraction to Aylena and his commitment to purity. In battle, he is a paladin through and through, with access to the full suite of healing spells as well as buffs to defence and a firm sword arm.

Kiryl is not the best practical choice of healer, though, because due to a quirk of the game’s AI he prefers to cast instant-death spells. The better healer in the game is one of the twins.

Meena/Porom: Yin and yang

The duality of white magic and black magic sometimes arises in the form of characters, too. In Dragon Quest IV we have Maya and Meena. One, a rambunctious, dancing mage, the other a reserved, fortune-telling healer.

Funnily enough, a very similar dynamic appears in Final Fantasy IV with the twins Porom and Palom. In both games, one twin casts offensive magic and the other heals the party.

Porom and her brother are just five years old, not typically a ideal age to undertake dangerous adventures. Magic is what excuses this questionable choice in companions. We can accept that magical aptitude can outpace physical development in this fantasy world.

And though small in stature, Porom and Palom are both large in heart. Once again, the black mage of the duo is the unruly one, the white mage more calculating, but neither is reserved: Polom is quite willing, eager even, to clip her brother around the ear when he deserves it, and make decisions for the group, who trust her judgement.

Porom is a reassuring early sign that healers can be proactive, full of energy, and take key roles in the story.

Rosa: The purest

The other main healer in Final Fantasy IV is Rosa, the first female white mage to be introduced in the Final Fantasy franchise.

Rosa’s character is simple and pure, denying ornamentation or complexity. She is the centre point on a love triangle involving the main character, Cecil, and his rival, Kain. She is not a princess, though is familiar with court life in her hometown of Baron. Her primary character traits are kindness and devotion to her friends (to Cecil especially). She rarely causes waves in the story except when she is immobilised by desert fever, or kidnapped by the villain — she is generally a passive character.

Rosa does not challenge our stereotypes but sits comfortably within them. Not all love interests are active characters. Rosa plays her part adequately, and can be seen as the foundation for many similar characters for decades to come. She is an important character in the franchise history. though not the most exciting one.

But now let’s try and answer a question: why “white mage” is a commonly chosen class for the female love interest?

Women and healing

Traditional ideas of femininity dovetail into the female healer archetype easily. The female physique doesn’t seem to fit a class that relies on big muscles, but there is no reason to disregard a magical class. On the same line of thinking, stereotypical female nature lends itself to a supportive role.

In 1996, we see these stereotypes in action. Princess Peach had been playable in an RPG before Super Mario RPG (1996). She could have become anything. A mage? A tank? But of course, Princess Peach is the healer. Resembling Moonbrooke and Rosa, she is a shoo-in for the role, ticking all the boxes of the stereotype.

Thankfully, from the start we see examples like Minwu, or Myau from Phantasy Star (1987) — in which game the only female character had a more physical role in battle. The stereotypes were not widespread or rigidly adhered to, but they did appear to have some staying power.

Cecil and Rosa: The cure couple

We’ve already seen how Final Fantasy IV contributed to JRPG healer lore, but there something important we haven’t even touched on yet: the main character is also a paladin, making a very rare example of both the main character and the love interest of the game being part of a healing clas.

It’s not too uncommon for a main character to have some healing potential. It’s a good way to balance the early portions of the game, when you might not have access to all characters. Alice from Phantasy Star was another capable healer. But usually the balanced main character can delegate to a dedicated (and more capable) healer later on, allowing the game’s poster character to show off more of their offensive abilities (and take more of the glory).

However, it’s unusual that the main character to be the party’s main healer. This trait is part of what gives Ness of Earthbound a unique flavour.

Aggressive healers (1994-2001)

With Cecil and Ness, we saw healers taking more mixed, offensive roles.

In Marle in Chrono Trigger (1995), we have a typical ranger, sporting a bow, a suite of healing spells, and complete with a feistier personality than any healer before her.

But why bring a crossbow when you can bring a gun? One of my favourite healers, Billy from Xenogears (1998), perfectly demonstrates how a character can be a “healer with a nasty bite”.

Make no mistake, he is kind, he is rational, and he is even a man of the cloth — a cleric in the most literal sense. On the other hand, he wields a pair of pistols like a cowboy, has a rather impressive damage output, and is certainly not afraid to take charge of a situation.

These are examples of healers becoming more active and less one-dimensional. The final examples in this article follow the same trend but take it in a different direction, resulting in one of the most popular healer subtypes.

A new archetype: the summoner

Once upon a time in the series, Final Fantasy summoners were an alternative black mage. Your summons were elemental bombs in a monster-themed wrapper. In Final Fantasy IV your strongest black mage, Rydia, was also your summoner, because why not: it’s roughly the same role.

However, Rydia’s descendants in spirit, Garnet and Eiko of Final Fantasy IX (2000), took a totally different approach. They were a healer/summoner hybrid, allowing them to do massive damage as well as massive healing. That made them a bit of a safe, more alike with Tellah than Rydia.

This new archetype proved popular, and was repeated in the very next game, for Yuna in Final Fantasy X (2001).

Up to this point, we have expected healers to have limited damage output, so giving them access to the most destructive abilities in the game is a pretty radical twist in itself.

But it goes a bit further than that: it gives the archetypical main female character something more to do in the story. Both Garnet and Yuna are similar in this respect, summoners in games where eidolons/aeons have more significance than in any game before. A very welcome change.

Yuna: The healer-saviour

You don’t have to look hard to see that Yuna could be an analogue to Jesus. She heals wounds, she is a preacher of sorts, and she is instructed to die for our sins — literally, sacrifice herself to defeat a monster called “Sin”. Yuna also walks on water and guides people’s souls to the afterlife.

She entirely fits the healer conventions, too. She is a princess (the daughter of high summoner Braska), she is quiet, kind, devoted and beautiful. She is Rosa in all these respects.

What makes her interesting is what she adds on top of those conventions. She does fight against a potentially tragic destiny, and she does wield unimaginable destructive power. It’s the combination that makes Yuna such a compelling character, and one of our favourite healers of all time.

Conclusions

So we haven’t come very far in 2000 years, but we came quite far in 20. The role of healer in 1991 was one-dimensional, but over time hybrid classes were allowed to flourish and the characters become more complex and had a greater role in the story.

Healers are as popular today as ever. One of the most popular characters in Final Fantasy XIV is Y’Shtola. One of the most popular characters in Overwatch is Mercy.

As long as there are games with combat, there will be a need for specialists to patch up our heroes. And sometimes, they are the heroes themselves.

List of Healers

These are the healers that appeared in this article. All are candidates for the best healers in JRPGs:

- Princess of Moonbrooke/Purin/Princessa (Dragon Quest II, 1987)

- Myau (Phantasy Star, 1987)

- Minwu (Final Fantasy II, 1988)

- Kiryl (Dragon Quest IV, 1990)

- Meena Mahabala (Dragon Quest IV, 1990)

- Porom (Final Fantasy IV, 1991)

- Rosa Joanna Farrell (Final Fantasy IV, 1991)

- Princess Peach (Super Mario RPG, 1996)

- Ness (Earthbound/Mother 2, 1994)

- Garnet Til Alexandros XVII (Final Fantasy IX, 2000)

- Eiko Carol (Final Fantasy IX, 2000)

- Yuna (Final Fantasy X, 2001)